Fairy

| (Faery, Fay, Fae, Wee Folk, Good Folk, Fair Folk) | |

|---|---|

|

Claudia by Sophie Anderson | |

| Creature | |

| Grouping | Pixies |

| Data | |

| First reported | In folklore |

| Country | Western European |

| Habitat | Woodland Gardens |

Fairies resemble various beings of other mythologies, though even folklore that uses the term fairy offers many definitions. Sometimes the term describes any magical creature, including goblins or gnomes: at other times, the term only describes a specific type of more ethereal creature.[2]

Etymology

The word fairy derives from Middle English faierie (also fayerye, feirie, fairie), a direct borrowing from Old French faerie (Modern French féerie) meaning the land, realm, or characteristic activity (i.e. enchantment) of the legendary people of folklore and romance called (in Old French) faie or fee (Modern French fée). This derived ultimately from Late Latin fata (one of the personified Fates, hence a guardian or tutelary spirit, hence a spirit in general); cf. Italian fata, Portuguese fada, Spanish hada of the same origin.Fata, although it became a feminine noun in the Romance languages, was originally the neuter plural ("the Fates") of fatum, past participle of the verb fari to speak, hence "thing spoken, decision, decree" or "prophetic declaration, prediction", hence "destiny, fate". It was used as the equivalent of the Greek Μοῖραι Moirai, the personified Fates who determined the course and ending of human life.

To the word faie was added the suffix -erie (Modern English -(e)ry), used to express either a place where something is found (fishery, heronry, nunnery) or a trade or typical activity engaged in by a person (cookery, midwifery, thievery). In later usage it generally applied to any kind of quality or activity associated with a particular sort of person, as in English knavery, roguery, witchery, wizardry.

Faie became Modern English fay "a fairy"; the word is, however, rarely used, although it is well known as part of the name of the legendary sorceress Morgan le Fay of Arthurian legend. Faierie became fairy, but with that spelling now almost exclusively referring to one of the legendary people, with the same meaning as fay. In the sense "land where fairies dwell", the distinctive and archaic spellings Faery and Faerie are often used. Faery is also used in the sense of "a fairy", and the back-formation fae, as an equivalent or substitute for fay is now sometimes seen.

The word fey, originally meaning "fated to die" or "having forebodings of death" (hence "visionary", "mad", and various other derived meanings) is completely unrelated, being from Old English fæge, Proto-Germanic *faigja- and Proto-Indo-European *poikyo-, whereas Latin fata comes from the Indo-European root *bhã- "speak". Due to the identical pronunciation of the two words, "fay" is sometimes misspelled "fey".

Characteristics

Fairies are generally described as human in appearance and having magical powers. Their origins are less clear in the folklore, being variously dead, or some form of demon, or a species completely independent of humans or angels.[3] Folklorists have suggested that their actual origin lies in a conquered race living in hiding,[4] or in religious beliefs that lost currency with the advent of Christianity.[5] These explanations are not necessarily incompatible, and they may be traceable to multiple sources.Much of the folklore about fairies revolves around protection from their malice, by such means as cold iron (iron is like poison to fairies, and they will not go near it) or charms of rowan and herbs, or avoiding offense by shunning locations known to be theirs.[6] In particular, folklore describes how to prevent the fairies from stealing babies and substituting changelings, and abducting older people as well.[7] Many folktales are told of fairies, and they appear as characters in stories from medieval tales of chivalry, to Victorian fairy tales, and up to the present day in modern literature.

In his manuscript, The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies, Reverend Robert Kirk, minister of the Parish of Aberfoyle, Stirling, Scotland, wrote in 1691:

These Siths or Fairies they call Sleagh Maith or the Good People...are said to be of middle nature between Man and Angel, as were Daemons thought to be of old; of intelligent fluidous Spirits, and light changeable bodies (lyke those called Astral) somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud, and best seen in twilight. These bodies be so pliable through the sublety of Spirits that agitate them, that they can make them appear or disappear at pleasure[8]Although in modern culture they are often depicted as young, sometimes winged, humanoids of small stature, they originally were depicted quite differently: tall, radiant, angelic beings or short, wizened trolls being two of the commonly mentioned forms. Diminutive fairies of one kind or another have been recorded for centuries, but occur alongside the human-sized beings; these have been depicted as ranging in size from very tiny up to the size of a human child.[9] Even with these small fairies, however, their small size may be magically assumed rather than constant.[10]

Wings, while common in Victorian and later artwork of fairies, are very rare in the folklore; even very small fairies flew with magic, sometimes flying on ragwort stems or the backs of birds.[11] Nowadays, fairies are often depicted with ordinary insect wings or butterfly wings.

Various animals have also been described as fairies. Sometimes this is the result of shape shifting on part of the fairy, as in the case of the selkie (seal people); others, like the kelpie and various black dogs, appear to stay more constant in form.[12]

In some folklore fairies have green eyes and often bite. Though they can confuse one with their words, fairies cannot lie. They hate being told 'thank you', as they see it as a sign of one forgetting the good deed done, and, instead, want something that will guarantee remembrance.[citation needed]

Origin of fairies

Folk beliefs

Dead

One popular belief was that they were the dead, or some subclass of the dead.[13] The Irish banshee (Irish Gaelic bean sí or Scottish Gaelic bean shìth, which both mean "fairy woman") is sometimes described as a ghost.[14] The northern English Cauld Lad of Hylton, though described as a murdered boy, is also described as a household sprite like a brownie,[15] much of the time a Barghest or Elf.[16] One tale recounted a man caught by the fairies, who found that whenever he looked steadily at one, the fairy was a dead neighbor of his.[17] This was among the most common views expressed by those who believed in fairies, although many of the informants would express the view with some doubts.[18]Elementals

Another view held that the fairies were an intelligent species, distinct from humans and angels.[19] In alchemy in particular they were regarded as elementals, such as gnomes and sylphs, as described by Paracelsus.[20] This is uncommon in folklore, but accounts describing the fairies as "spirits of the air" have been found popularly.[21]Demoted angels

A third belief held that they were a class of "demoted" angels.[22] One popular story held that when the angels revolted, God ordered the gates shut; those still in heaven remained angels, those in hell became devils, and those caught in between became fairies.[23] Others held that they had been thrown out of heaven, not being good enough, but they were not evil enough for hell.[24] This may explain the tradition that they had to pay a "teind" or tithe to Hell. As fallen angels, though not quite devils, they could be seen as subject of the Devil.[25] For a similar concept in Persian mythology, see Peri.Demons

A fourth belief was the fairies were demons entirely.[26] This belief became much more popular with the growth of Puritanism.[27] The hobgoblin, once a friendly household spirit, became a wicked goblin.[28] Dealing with fairies was in some cases considered a form of witchcraft and punished as such in this era.[29] Disassociating himself from such evils may be why Oberon, in A Midsummer Night's Dream, carefully observed that neither he nor his court feared the church bells.[30]The belief in their angelic nature was less common than that they were the dead, but still found popularity, especially in Theosophist circles.[31][32] Informants who described their nature sometimes held aspects of both the third and the fourth view, or observed that the matter was disputed.[31]

Humans

A less-common belief was that the fairies were actually humans; one folktale recounts how a woman had hidden some of her children from God, and then looked for them in vain, because they had become the hidden people, the fairies. This is parallel to a more developed tale, of the origin of the Scandinavian huldra.[31]Babies' laughs

A story of the origin of fairies appears in a chapter about Peter Pan in J. M. Barrie's 1902 novel The Little White Bird, and was incorporated into his later works about the character. Barrie wrote, "When the first baby laughed for the first time, his laugh broke into a million pieces, and they all went skipping about. That was the beginning of fairies."[33]Pagan deities

Many of the Irish tales of the Tuatha Dé Danann refer to these beings as fairies, though in more ancient times they were regarded as goddesses and gods. The Tuatha Dé Danann were spoken of as having come from islands in the north of the world or, in other sources, from the sky. After being defeated in a series of battles with other otherworldly beings, and then by the ancestors of the current Irish people, they were said to have withdrawn to the sídhe (fairy mounds), where they lived on in popular imagination as "fairies."[citation needed]Sources of beliefs

One common theme found among the Celtic nations describes a race of diminutive people who had been driven into hiding by invading humans. They came to be seen as another race, or possibly spirits, and were believed to live in an Otherworld that was variously described as existing underground, in hidden hills (many of which were ancient burial mounds), or across the Western Sea.[4]

In old Celtic fairy lore the sidhe (fairy folk) are immortals living in the ancient barrows and cairns. The Tuatha de Danaan are associated with several Otherworld realms including Mag Mell (the Pleasant Plain), Emain Ablach (the Fortress of Apples or the Land of Promise or the Isle of Women), and the Tir na nÓg (the Land of Youth).[34]

The concept of the Otherworld is also associated with the Isle of Apples, known as Avalon in the Arthurian mythos (often equated with Ablach Emain). Here we find the Silver Bough that allowed a living mortal to enter and withdraw from the Otherworld or Land of the Gods. According to legend, the Fairy Queen sometimes offered the branch to worthy mortals, granting them safe passage and food during their stay.

Some 19th century archaeologists thought they had found underground rooms in the Orkney islands resembling the Elfland in Childe Rowland.[35] In popular folklore, flint arrowheads from the Stone Age were attributed to the fairies as "elf-shot".[36] The fairies' fear of iron was attributed to the invaders having iron weapons, whereas the inhabitants had only flint and were therefore easily defeated in physical battle. Their green clothing and underground homes were credited to their need to hide and camouflage themselves from hostile humans, and their use of magic a necessary skill for combating those with superior weaponry.[4] In Victorian beliefs of evolution, cannibalism among "ogres" was attributed to memories of more savage races, still practicing it alongside "superior" races that had abandoned it.[37] Selkies, described in fairy tales as shapeshifting seal people, were attributed to memories of skin-clad "primitive" people traveling in kayaks.[4] African pygmies were put forth as an example of a race that had previously existed over larger stretches of territory, but come to be scarce and semi-mythical with the passage of time and prominence of other tribes and races.[38]

Christianised pagan deities

Another theory is that the fairies were originally worshiped as gods, but with the coming of Christianity, they lived on, in a dwindled state of power, in folk belief. In this particular time, fairies were reputed by the church as being 'evil' beings. Many beings who are described as deities in older tales are described as "fairies" in more recent writings.[5] Victorian explanations of mythology, which accounted for all gods as metaphors for natural events that had come to be taken literally, explained them as metaphors for the night sky and stars.[39] According to this theory, fairies are personified aspects of nature and deified abstract concepts such as ‘love’ and ‘victory’ in the pantheon of the particular form of animistic nature worship reconstructed as the religion of Ancient Western Europe.[40]Spirits of the dead

A third theory was that the fairies were a folkloric belief concerning the dead. This noted many common points of belief, such as the same legends being told of ghosts and fairies, the sídhe in actuality being burial mounds, it being dangerous to eat food in both Fairyland and Hades, and both the dead and fairies living underground.[41]Fairies in literature and legend

Practical beliefs and protection

Classic representation of a small fairy with butterfly wings commonly used in modern times. Luis Ricardo Falero, 1888.

Literature

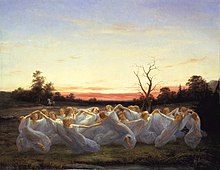

Fairies in art

See also: Fairy painting

"Momentarily, she was trans-formed into a little, exquisitely beautiful fairy". Illustration from Alfred Smedberg's The Seven Wishes among Gnomes and Trolls by John Bauer.

No comments:

Post a Comment